Asia Contemporary Art Week's annual forum, Field Meeting, was staged outside of New York for the first time in 2019, with Take 6: Thinking Collections hosted by Alserkal Avenue in Dubai, concurrent to Quoz Arts Fest (25–26 January 2019). The two-day forum unfolded inside Concrete, Alserkal's impressive OMA-designed space, with pop-up exhibitions presented in warehouses 46 and 47, and performances staged in warehouse 58. The event, described by curator and ACAW Director Leeza Ahmady as a 'studio visit on a communal scale', sought to decategorise 'the word "collections" away from the ever-burgeoning global art market to claim the artist as the first collector.' A decategorisation that was perfectly enacted when artist Arahmaiani Feisal concluded Field Meeting Take 6 with a performance of 'Breaking Words', which saw audience members write key words onto white plates, and Feisal smashing them onto a wall.

Ocula's editor-in-chief, Stephanie Bailey, was invited to deliver the closing remarks to the event, which involved Bailey constructing a report and a summary in real-time during the two-day gathering. Below is a copy of her remarks, with some edits and additions.

So here we are, and here I am, tasked with the daunting challenge to deliver final remarks after a dense, thought-filled two days. Thanks to Leeza Ahmady, Alserkal Avenue, and all presenters, respondents, and pop-up artists for contributing to this gathering—and of course, to the audience who have stayed the course.

En route to Dubai, I thought about Hassan Sharif, a pioneer of the U.A.E. art world, when thinking about how I might possibly capture the conversations expressed in this room, which had me writing up to the moment it was time to come on stage. Sharif once said, 'My whole body moves so that I am always facing the future, whatever it may hold'—a perspective that fits with the open-ended way 'collections' have been thought through in this meeting, driven by an understanding of collecting as a way-finding practice, whether as an artist, writer, curator, administrator, or editor.

Sharif was a quintessential artist-collector. On an exhibition he staged here at Alserkal Avenue in 2015, which included a giant column of magazine pages strung together from the ceiling to the floor, he talked about images and their ability to stimulate people in a consumerist society, wondering if this had always been their function. He pointed to the shopping mall as an example—'an important social vehicle in the U.A.E.', where 'everything ... is there to stimulate us.' He called this a horizontal, postmodernist existence, using the mangrove to diagram his point: 'Mangroves', he said, 'grow laterally as much as vertically, their branches dipping into the ground and initiating new roots.'

This came to mind when listening to Alserkal Avenue Director Vilma Jurkute's opening remarks to this forum, which she hoped might 'produce, or perhaps redefine or renegotiate, the new borders of knowledge geography and not just geography itself.'

Jurkute's distinction felt important during the first morning session, 'Inside Out: The Artist as Collector', when artist Nikhil Chopra—after drawing a tempestuous sea out of red lipstick on the walls of warehouse 58—talked about the role of water in understanding where he is. He described growing up in Dubai and feeling as if he could see Bombay as he gazed out to the sea, only to end up as an adult in Goa, looking out at the water again and feeling as if the Arabian Gulf was within reach.

The sea, as Chopra noted, is thick with history—colonial, cultural, transactional, personal—and he says he becomes liquid when he looks at it. I wondered if it was because the sea is like a mirror of his own immeasurable fluidity: the kind that brings to mind a Greek song about Constantinople, from where so many Greeks were expelled in the early 20th century, whose lyrics describe wanting to drink the entire Bosporus strait, a watery boundary between Asia and Europe, because the world's borders are changing within the person singing the song.

This embodied experience came to mind when artist Heman Chong, in his talk 'Foreign Affairs', described how his status as half-Malaysian and half-Singaporean left him a guest in Singapore, his mother country, until he completed national service and was given the choice of renouncing his Malaysian identity to become a citizen. In this context, Chong's ongoing Foreign Affairs project, of photographing the backdoors of national embassies around the world, not only tests the limits of infrastructure when thinking about a nation-state as a system, as he explained; but rejects those infrastructures when it comes to the narratives they produce, which deny Chong the fluidity that encapsulates not only who he is, but the region where he was born.

'Nationalism is a kind of fiction', Chong said; 'it produces an agreement about what is real and what is not.' So, he rejects this fiction by engaging in his own form of writing, which challenges the linear narrative as 'a collection of ideas and the negotiations of those ideas between people—a process that is not that different to nation-building or legality.'

The idea of narrative as a framing device was easily transferred to what Leeza Ahmady described as the art world's tendency to categorise and claim terms in the discussion that followed. Terms like the word being considered in this meeting, and its association—alongside the role of collector as buyer—with the accelerationist global art market. As Ahmady noted, this simple word exists in many forms and belongs to many fields and people. Thus, Field Meeting Take 6 has been as much about un-thinking collections as it has been about thinking them, in order to create a productive multiplicity as opposed to a simplified consensus.

This might explain why the body emerged as a constant receptacle throughout. As Chopra said, 'I am my own mini-museum—my body is a container of all my experiences, interactions, and relationships', and 'I am interested in twisting ideas of who I am and where I can go with this story.' Artist Ranbir Kaleka took this story to his roots, as a child living in productive isolation in a remote home, who became a collector of non-events, feeling 'most comfortable in an in-between grey space'—a space that seems to connect with everyone here, in one way or another.

In this first session's discussion, which turned to the spectrum of fiction and non-fiction, the in-between space emerged as a site of possibility. Kaleka talked about patterns emerging when woodwork or walls age—an experience of looking not unlike seeing shapes in clouds. He called this mode of seeing 'a desire to break the wall', 'go beyond it', 'and/or make it permeable'. Chopra also touched on this when describing his preoccupation with looking for infinity in a flat surface, which could be conflated with what he said about the vastness of the sea, which invokes the impossibility of knowing something entirely—including your place in the world.

This tension between knowing and not knowing permeates that in-between space, with a pressure Kaleka called political. 'When I reach a point where the tension is slightly released in my own body', he said, 'it is necessary that I do not simplify it.' Chong elaborated on why when talking about turning his collection of embassy door photos into grid-like patterns that he could make into prints that cover everyday objects—'I want the invisible, unsaid, and sinister to be on everything', he said. After all, when something becomes visible, it can be complicated, broken, transcended, and/or overcome.

In the afternoon session, 'Pendulum Swings & Spheres of Influence', the in-between became a movement—a swinging pendulum of inescapable, almost inherent, contradiction, as reflected in the rapid-fire montages that populated the screen during artist Bassem Saad and writer Edwin Nasr's lecture-performance, 'This Ritual I Wish You Could See (Render & File)'. This visualisation of the aesthetic violence, generic realism, and ritual performance encoded into VR games produced by the U.S. army and Hezbollah for training purposes performed a dialectics of polarity, which the artists described when talking about Hezbollah's positioning of itself as a counter hegemon, essentially using the same technologies as its hegemonic enemy, and thus rendering it as violent as its perceived opposite. To push the point, Saad and Nasr described putting the imagery that they collected, associated with both forces, on the same plane so as to mess with them altogether—essentially bringing them into equivalence.

The result was the picturing of a cycle that seems embedded into modernity, which Chong touched on when talking about the cultural warfare Singapore learned during the Cold War, whereby national 'sovereignty is constructed on the telling and/or re-telling of [one's] neighbours' stories as lesser'. A dynamic that connected with artist Khadim Ali's history of demonology and its direct association with the dehumanisation of an entire group of people, the Hazara of Afghanistan; with Ali's imagery, as demonstrated in the 2014 'Transitions/Evacuation' and 'The Arrivals' series, articulating how archetypal binaries like good and evil are transposed onto actual bodies.

Thus, this afternoon session picked up where the morning left off. Collecting—be it through the accumulation of images that are arranged to articulate a line of research, itself a form of collecting, or the accumulation of a group of bodies, like ours in this room—produces visibility, which increases knowledge, offers a truer, more complex view of the world, and rejects reductive dynamics that have all too often shaped and divided it.

This was demonstrated in artist Umber Majeed's lecture-performance, 'Atomi Daamaki Wali Mohabbat (The Atomically Explosive Love)', charting the nationalism embedded into the development of nuclear power in Pakistan, and the conflation of this power with religious ideology. Majeed's lecture was accompanied by a video animation that made full use of green-screen-slash-uranium green as an abstract, monochromatic catch-all—not unlike the sea as a site of infinite mirroring—for the complex dynamics that have fed into the present, when the internet has become a site where political and historical narratives compete and collide. Edited into the video were photographs celebrating the flora of Pakistan by Majeed's grandfather, which were juxtaposed with nuclear plumage—a positioning of modernisation as a cycle of creation and destruction: or, to paraphrase the artist, a matter of 'boom to bloom', and back again.

As with Saad and Nasr, Majeed's project accumulates moments in order to either 'make sense of it all, or own up to the fact that nothing is making sense.' On the performance format, she described a space between her physical body and her script, highlighting 'tensions between what is performed and what is enacted'. These tensions illuminated one idea: objectively speaking, nationalism is a form of performed or enacted love—the emotion is neither good nor bad, but simply a force to be reckoned with.

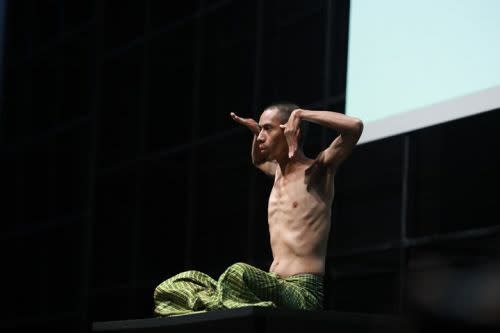

Moe Satt's intervention ('Face & Fingers') that rounded off this session—for which he performed 108 hand gestures around his face and invited audience members to mirror him—expressed this force, when thinking about his admission that he does not enjoy performing on a stage, or in a black box like the one we are in; which relates to the word that this meeting is trying to decategorise, and the format in which this decategorisation is taking place. It all comes down to how we choose to use a space, a meeting, a platform—just as a word means as much as the meaning we give it. To quote Kaleka, 'a horse is never a horse, but a thought'.

The idea that something is only as much as what you think it is connects with Chopra's observation of the city as a space that engineers rigid behaviour, and the countering of this perceivied condition in ST Luk's introduction to the transformative architectural practice of Arakawa and Madeline Gins, which included a short screening of Nobu Yamaoka's documentary, Children Who Won't Die. Yamaoka's documentary focuses on the Reversible Destiny Lofts, a residential complex realised in 2005 that challenges normative modes of living through unconventional design, which brought the focus back to the body in the context of this meeting; just as Arahmaiani Feisal's presentation took the discussion back to where it started—with the artist as the original collector—by reciting an artist's manifesto towards the end of day one.

Everything begins with a gesture, or a collection of them: Moe Satt made that quite clear in his performance on day two, 'F n' F & Other Side of the Revolution', which opened with Satt inviting people to stamp their hands in ink and mark his upper body, and culminated in an invitation to the audience to shoot rubber bands at one another, which inevitably ended in laughter.

So, we return to the body as collector: something that, like a collection, can be many things. As Ahmady explained, the afternoon session during which Majeed, Saad, Nasr, Satt, and Ali spoke, was about the landscape as a body—a site of being and collectivity, where dual forces come up against one another. Also included in this line-up was Alexis Destoop, whose lecture-performance, 'Phantom Sun', was based on a 2017 video installation exploring restricted military and industrial sites along the Russian-Norway border. As Destoop noted, while the images of this landscape look bleak, there is a contradictory narrative to the region in question, which he says is also 'a place of incredible beauty', with 'an indigenous culture that is still alive'. In that respect, Destoop said he was able 'to connect to stories that are very old' and 'very deep'—'one aspect of what lies beyond the pendulum.'

Deep time resonated in the first day's final session, 'Modes of Being: Ideologies and Space as Malleable Entities', which opened with Sam Samiee introducing Adab—an all-encompassing Persian term encapsulating education, culture, and ethics, which was defined in discussion as more of a practice—to consider the practice of painting as a toolbox through which to 'come up with an embodied discourse of visual arts, rituals, usage of language and all that it entails'.

Samiee's talk considered art as comprising multiple canons, and positioned history as visual, material, embodied, and non-linear. These ideas resonated with Chongbin Zheng's presentation, which illustrated a phenomenological practice that seeks to render space as alive and malleable through material interventions that encourage perceptive experience: precisely what this particular session was about.

On his project Wall of Skies at the Shanghai Biennale in 2016, Zheng talked about the various elements that went into the piece, including the ink on paper works that were mounted on a wall constructed with undulating angles, and demonstrated the causality of painting with ink—as it seeps into paper it performs a cartography of its own, thus drawing a natural terrain out of a blank page. Such material map-making came through in Burçak Bingöl's introduction to a 16th-century ceramic panel by Shah Quli at Topkapi Palace, which she described as a point of departure, or entry, into research that maps a history of material—and thus cultural—exchange between Persia, China, and Turkey.

These presentations would foreground River Lin's performance on day two, in which the dancer Wen-Chung Lin renegotiated Tino Sehgal's 20 Minutes for the 20th Century performance from 1999, which collaged 20 choreographies from seminal 20th-century performers. Lin's rendition brought Sehgal's piece into a 21st century, Asian context—hence the title, '20 Minutes for the 20th Century...But Asian'—by blending forms of dance that include Chinese folk dance, yoga, and other styles. Not to mention M+ curator Pi Li's presentation of Huang Yong Ping's washing machine works, including The History of Chinese Painting and a Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes, for which Chinese and Western art history books were rendered a single mound of merged text.

On the morning of the second day, mapping as an expansive act of unfolding was situated in the institution—as elaborated by Lara Day in her presentation about her work as senior manager of digital and cross-platform content at M+, which mentioned imagining and inventing new canons of art history through the creation of an open-access digital platform rooted in the accessibility of M+'s collection, and the telling of stories, be they about the work being done at the museum or the ideas forming in the minds of creative thinkers.

Creating an open platform to tell stories also describes Field Meeting 6's series of pop-up installations, which expands on all the ideas shared here, from Yuan Gao's beautiful animation composed of acrylic paintings and works on paper, Lunar Dial and Human Smoke, Amina Ahmed's homage to a sewing collective formed by her mother before she was born, Un-Furling, and Ali Shayesteh's text-based works based on the remains of ten years' worth of notes and rag fragments he found in his studio.

Bringing such works together, noted participating artist Nadira Husain (showing Cosmic Trips: fabric paintings merging characters from Egyptian mythology, heroic epics, and cartoons) adds more layers to those that already exist in each individual work. The same could be said of this symposium and what it has done to fragment a single word. Take Vladislav Sludskiy and Olga Veselova's Limited Liability Pavilion 4.0, a presentation of works taken from 17 private collections in Kazakhstan belonging to artists who have taken it upon themselves to archive their practice and the practice of others; or the garments on view from Zarif Design Center in Kabul, which merges traditional, handcrafted Afghan design with modern aesthetics through fair-trade practices.

Of course, that I have not been able to discuss all works and presentations in detail speaks to something Ahmady pointed out—that collecting is also about selecting, and as inclusive as we would hope to be when it comes to decategorising the term, things inevitably get left out.

This process of editing was articulated by Sam Samiee in the final discussion among pop-up artists Rana Dehghan (showing a site-specific installation that featured sculpted lamb skulls placed on top of an image of Donald Trump, Heads); Bingyi (presenting an edited excerpt of the film trilogy Ruins, which conjures the memories of the inhabitants of Beijing's historic, inner-city hutongs); Bahman Mohammadi (whose paintings on photographic paper refer to studies on human palaeoanthropology); Hasanul Isyraf Idris (showing a stunning re-telling of an island narrative through a collection of sci-fi inflected illustrations rendered in neon colours on black paper, Higher Order of Love); and Haiyang Wang (who presented a collection of illustrations on paper that fed into the animation The Birth of the Word, to the Demise of the Bird, also on display).

Professors Sandra Skurvida and Natasha Degen also raised this issue of omission in their presentation during the penultimate session of day two, which considered best practices for intercultural study as an experiential collection of knowledge, noting the act of selection along with the connection-making that comes with curatorial work.

Referring to the rise of the so-called Art Tour as a kind of neocolonial enterprise, and the colonial roots of international education in the Arab world, Skurvida and Degen posed the question of how to keep things open when it comes to devising new forms of intercultural collaboration, which kind of answers the question this session posed—who collects and why—in that collecting, as it has unfolded in these two days, appears open-ended as both a practice and as a definition. At the same time, the question of openness is a notion that itself could well require an entire conference to define in today's global, multipolar art world; something that came out in the conversation that followed this session, which Ahmady rounded up by bringing back into frame the tensions between knowing and not knowing that were discussed on day one.

Offering a different response to who collects and why, Wong Kit Yi's lecture-performance 'Magic Wands, Batons and DNA' proposed a redefinition of the traditional artist-collector relationship, demonstrating how artists can manipulate existing modes of collecting and collection-building by employing the market as part of the artistic process, rather than allowing it to absorb the work.

Wong introduced her Art Basel Hong Kong booth with a.m. space in 2018, conceived as a social space with a karaoke spot, as well as a DNA sampling station, for which the artist's collectors might literally become part of her practice—a reconfiguration of an existing format to suit her position, and what Wong described as a step to reconfigure the art system in general. Thus, Field Meeting 6 ended as it began, with an artist as a collector, who uses the collection as a space of renegotiation that works for rather than against her.

Throughout Field Meeting 6, collecting—as an artistic and curatorial practice—emerged as a form of resisting and enabling. It is the production of a threshold; the opening of a terrain; a way through the dark; a form of sharing, opening up, and evolving. Collecting can bend space and time, and reimagine the future in the process.

To borrow Francesca Recchia's moving reading about gathering stories in Kabul, which I am going to sample to offer one possible definition of collecting, and which also sums up how it felt to write this text on site and in real-time: a collection 'is about curiosity, adrenaline, the sense of the limit, the challenge of the unknown.'—[O]