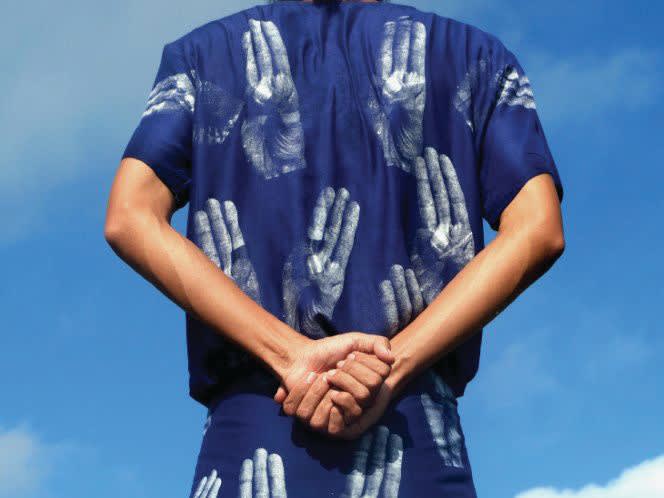

"Ninety-five days in prison have only strengthened Moe Satt’s resolve to resist the Tatmadaw military dictatorship that seized control of Myanmar in a coup this February.

One of the country’s best-known artists, Moe Satt was detained during a protest on Armed Forces Day on 27 March. He says that after a car of police and soldiers arrived at the protest, “we ran away and hid in a nearby building. But they searched the entire area and the whole building from the ground floor to the top; we were hiding on the ninth floor. Finally, they found us. After a few hours at a police station and two nights in the Interrogation Camp [a military jail], I spent 38 days in an isolation ward at Insein [Yangon’s notorious central prison], then 55 days in a meditation ward there.”

Moe Satt and his companions were charged with Myanmar’s Code 505-A outlawing reports or rumours that are damaging to the military. He was arrested along with eight others—“five poets, one designer and two young people”—during a year of protests that has also seen the detention of film directors, musicians, actors and actresses, writers, and the rector of a university of art and culture, he says."