This photo essay is part of our dossier "Young voices on the rise - Youth and democracy in the Asia-Pacific region".

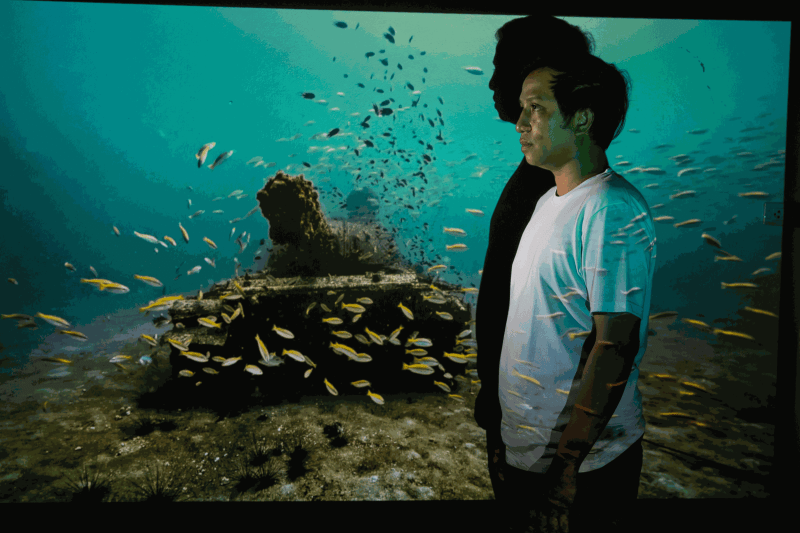

In the watery deep lie two dozen military tanks. In 2010, soldiers had dumped them into the ocean off the coast of Southern Thailand, purportedly to make artificial coral reefs. Eight years later, an artist holds an exhibition of this forgotten initiative. Rusting away in the Gulf, fish swim through the hatch and hulls, but only the tips of the guns are crusted with coral. (You Lead Me Down to the Ocean, Tada Hengsapkul, 2018)

If not for Tada Hengsapkul, these telling relics of Thai history would have been drowned by time or given a pro-establishment footnote in a government list of projects. But to that possibility - and to all state authoritarianism, bureaucracy, and all things groove-stifling, modern artist Tada Hengsapkul gives a big ol' middle finger - in the form of art installations, of course.

One of the most radical political artists in the Thai scene, the 34-year-old ties together nationalism, often-ugly politics, and the bruises of the Cold War in provocative, thought-provoking art.

Dividing himself into two bodies

"They wanted me to take a photo of a Buddha image? Fine, here's one on the back of a truck. They want a photo of a temple? Fine, here's a photo with the sky, with just a spire tip visible."

Tada was a shutterbug and anti-establishment teen growing up in the northeastern province of Khorat, often skipping class to pick books to read and computer to program at home. When he won a photography contest with Lomography at 17, he realized he didn't need to "rely on the system" to be successful.

It took some persuasion to get Tada to attend university in Bangkok ("I didn't think art needed to be studied"). But, soon, the young man - who had boycotted KFC and pizza for anti-capitalist reasons - found himself in the bastion of bureaucracy and consumerism as a photography student at Pohchang Academy of Arts.

Other students might have learned how to take perfectly symmetrical snaps of temples and gotten an A through winning government photography contests. But not Tada.

"I was always fighting with my ultra-conservative professors," he recalls. "To get a good grade you need to take photos of monks or temples against the sunset."

Oh, they wanted conventional "good Buddhist" photos, did they? So Tada took pictures of monks and Buddha images loaded on the back of trucks (named "Buddha Speeding Forward") and a plain sky with just the needle spire of a temple.

"I had to divide myself into two bodies: one to send stuff to the professor so I could graduate, and the other made art."

The snake and the birds

A listless man painted red sits in his stark bedroom - there is nowhere to look outside as a political campaign poster blocks the view. Outside, another man in a tewada angel costume aims his sniper, ceremonial trays around him filled with blood. ("Parade, 2013")

After university, Tada held exhibitions and dove deep into the circles of political activists, poets, and other artists, carousing together in liberal like-mindedness and his DJ music. But in the 2010 military crackdown of "Red Shirt" protesters in Bangkok, one of Tada's friends, 17-year-old Samaphan "Cher" Srithep, was killed with a single sniper bullet.

Cher's father Pansak Srithep, one of Tada's drinking buddies, has been protesting against the government and military ever since his son's death. More than a decade on, the family still has not received justice. No one was ever held accountable for the death of the teenager.

"My work has always been political," Tada says. "But after Cher's death, it was more about recording what had happened, usually things that this fucking terrible state wants to make disappear."

His "Parade" (2013) photos were a direct result of this post-2010 political agony, works on the bearing down of authoritarian power on people and their bodies - and a desire to commit them to memory. One photo was of a homeless man Tada befriended and who the police beat up so severely that he had brain damage. The man asked to urinate on a book of law, which Tada photographed. The man has since passed away.

Another is a photo of snakes ready to strike at birds laying down in a bed of yellow flowers. "If no one is recording events, whether in art, music, poems, the news, the snake will just relax on the flowers and feast [on the birds]," Tada says.

After the 2014 coup and the death of Thailand's King Rama IX in 2016, Tada created a new political interactive exhibition, "The Shards that Would Shatter at Touch" (2017).

In the whiteness of a gallery room, Tada hung 40 pieces of cloth covered with thermochromic black paint. Visitors were instructed to hug the fabric until their body heat would cause the paint to change colour. Slowly, it would reveal a photo of one of Thailand's many political prisoners or victims of state violence. The exhibition then provided more information about each of them. One of the 40 was his friend Cher.

Tada remembers that some visitors thought the texts were works of fiction. "They didn't know that these were real. I wanted people to get close to the facts by physically hugging them, and feeling them through the delicateness of human touch."

Fellow artist and friend Latthapon Korkiatarkul said that "Shards" was one of the exhibitions best representative of Tada's personality.

"He is actually a very kind and down-to-earth person who's always looking to make bonds with others," Latthapon says. "So getting people to feel a connection to others who have been made to disappear via body heat - that was so him. It was his way of showing that he cared about people who were untreated unfairly by the law."

In the current political climate where police violence against pro-democracy protesters has been increasingly rampant, Tada says, his past works still ring true. "If I redid this exhibition today, the list would be longer than a kite's tail. The cloth would be all over the walls and floors."

Bomb crater village

A photo of a lovely woman in 1960s mod makeup warps and drips and melts over a space of 14 minutes. Nearby, mortar tail fins from the Vietnam War salvaged from scrap waste are arranged into the word "bliss." ("Under the Same Sky," 2016)

Being a son of the Northeast, Tada's work has also focused on recording the region's under-examined past. The exhibition "Under the Same Sky" (2016) tied together almost-forgotten memories of his own family, the region's role in the Cold War, and even the effects of the US Army bases located there during the Vietnam War.

The melting woman is a photo of his aunt that Tada found at home. He learned only in adulthood that she killed herself after her American soldier sweetheart was shipped back home in 1974.

While scavenging for scrap metal to use in his exhibition, he found many Vietnam War-era mortar shells. He placed them together to form the word "bliss" and also melted them into a globe. The bombs were made in the same year his aunt took her life.

"I wanted to talk about the Vietnam War and its effects on Thailand, most importantly about how the US put down a system of education, bureaucracy, and propaganda that continues till today," Tada says. "The sentiment then was that if communist ideas come in, then religion and monarchy would be gone."

The artwork includes photos of the so-called Bomb Crater Village in Khorat, a long-abandoned Vietnam War-era US military base. After looking for it for years, Tada finally found it by following a local man down a dirt road. A solitary radio tower, a flagpole that once flew the Stars and Stripes, a long line of concrete columns that once told pilots where to drop unused bombs so they could land - all these are now decaying, swallowed by grass.

The artwork also featured photos of the St.Theresa Baan Nonkaew Catholic Church in Khorat. On 2 March 1942, villagers shot at a French priest through the walls of his home (which hit the Thai priest and killed him instead) and burned down the original church structure. Anti-French sentiment was at a high due to the Franco-Thai War. Today, the priest's home hosts a small museum.

All of these episodes of Thailand's history - its involvement in the Vietnam War, the housing of US bases in the Northeast, the xenophobic killing - are hardly ever taught in the public schools and are unknown to most Thais.

"The Thai educational system is made by rightwing nationalists," Tada says. "Human rights are absent, as are episodes about the violent things we did. Those are taboo."

"Like with the church killing, they wouldn't want to teach about it because it's embarrassing - a Buddhist was violent to a person of a different faith. They don't mention our support of the US in the Vietnam War, because then people will know we supported killing."

In recent years, Siamese Revolution-era monuments in Thailand have been disappearing - most notably the 1932 Revolution Plaque, uprooted quietly in the night. But in the grasses of the northeastern region, "monuments" of Thailand's unsavoury history are made to disappear with few people noticing.

"They didn't need to try to make it forgotten or demolish it, it's disintegrating on its own," Tada says of the decaying Bomb Crater Village.

A couple of years ago, he gave the site's location to a local historic preservation group. Upon arriving, they messaged, telling him that there was nothing left to preserve.

To those still underwater

"I will fight for the queen. ... I shot at least twenty Viet Cong dead." "My dear, we still haven't gotten the benefits from your service, it's getting hard to survive." ("You Lead Me Down, to the Ocean," 2018)

In 1987, Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda and then-crown prince Vajiralongkorn took an official state visit to China to purchase tanks as a sign of friendship. But the Thai military could not fix the second-hand tanks, so they sat unused in Khorat for years. Finally, in 2010, they were dumped into the ocean off the coast of Narathiwat province - as part of a royal project to produce artificial coral reefs to better the lives of fishermen.

In "You Lead Me Down, to the Ocean" (2018), Tada directed underwater photographers to capture these tanks - dumped in a haphazard circle, with little coral formed after years. Displayed with this footage are letters written by Thai soldiers in the Vietnam War, and warped photos from the era are stretched into tentacles that reach into present-day nudes.

The work was his defiance against Cold War era nationalism and propaganda, which he believes has benefited the people little over the years: "It's become the heritage of people living now," he says. "Like the tanks, people in the entire country are now left underwater in the dark depths. So this work is dedicated to those still under the water."

"His sunken tanks were almost a meditative work. I was immediately drawn to the story behind it," says Abdul Abdullah, 34, a contemporary artist from Australia and one of Tada's closest friends. "He has a bravery and 'fuck-you-all' attitude in the face of overwhelming authority that I was inspired by."

This political fervour has transferred to Tada's recent support of the pro-democracy protests that have been raging since 2020. He participated in a performance art at Sanam Luang, Bangkok's royal square, of about 90 people that commemorated the 2010 Red Shirt crackdown.

I support the truth, people who speak it, and the youth," Tada says. "People have been stepped on since birth and they want to change the future. It's the state that must give way."

Since the pandemic, Tada has been unable to exhibit new work. So instead, he's spending time giving out aid relief packages to those needing food, especially the homeless, around Bangkok twice a week. "There are so many. And the government won't help them, because they have no citizen ID card," says Lattapon, who helps Tada crowdfund and distribute the packages.

He plans to open a new exhibition soon at MAIELIE Art Gallery, a science fiction-themed work about people 15 years into the future coming to visit the present time.

"He's got a sense of bravery and a punk mentality, like 'I'll figure out how to do it and I'll do it myself," Abdullah says."There are not that many hardhitting younger artists with this 'fuck you' mentality. Tada's got it, and it's gonna serve him well."

This piece was produced by HaRDstories with the support of Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union. Edited by Fabian Drahmoune.