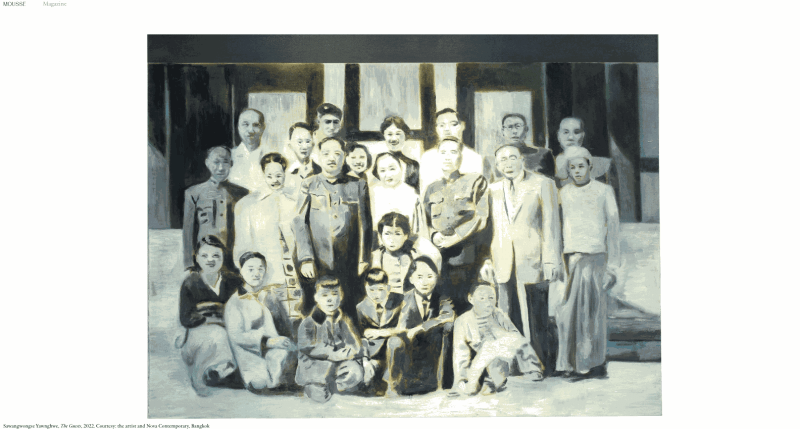

"Yawnghwe began making paintings of his own father, a military man, only after his death, combing through the archives to make sense of his family history and coming of age in perpetual exile. The trans guration of found photographs by his own hand is akin to the Portraits from Behind, an exhibition of paintings at Gallery Exit by Hong Kong artist Chow Chun Fai, made during the 2019 Be Water Revolution and shown in March the year a er, marking an inability to project past a totalizing present. Now, as Yawnghwe’s mother takes on years, he has painted another series shown at Nova Contemporary in Bangkok titled The Broken White Umbrella. At its core are paintings based on eight archival images from early mid-twentieth-century Burma painted in pale pastels with the same fuzz of old photographs, eclipsed by bands of color. The bands make the edge of the canvas appear hardened, fading the image from our view the closer we step to it. People call each other when they can with news about the most recent military action or assassination attempt; about friends who are being targeted, showing proof of acquaintances who were slipping from town to town; and signs that guerillas had taken over the neighboring abandoned buildings. Family and friends keep breaking the news to one another. Abroad, Yawnghwe can find evidence for this intel in the headlines and clippings in real time, though with different names and faces. For him, this news could be grounded in the aftermath of the 1962 coup, which led to his family’s first exile. Receipts reconciled between decades, suffocating the resistance with brackets drawn in blood. In homage to a protest tactic whereby people hang women’s undergarments on clotheslines across streets, both to block the view of military personnel and to deter them from proceeding (it is believed one’s masculinity will be compromised), he made a textile work titled 22022021, Yawnghwe Office in Exile (2021)—shown at Modka Beiroet, Zutphen (2021), and later at Kathmandu Triennale 2077 (2022)—a recreation of these billowing so blockades, named for the start date of the mass uprising against the coup."