Creating new rituals for a world in flux

Stephanie Bailey, Art Basel , 19 January 2024

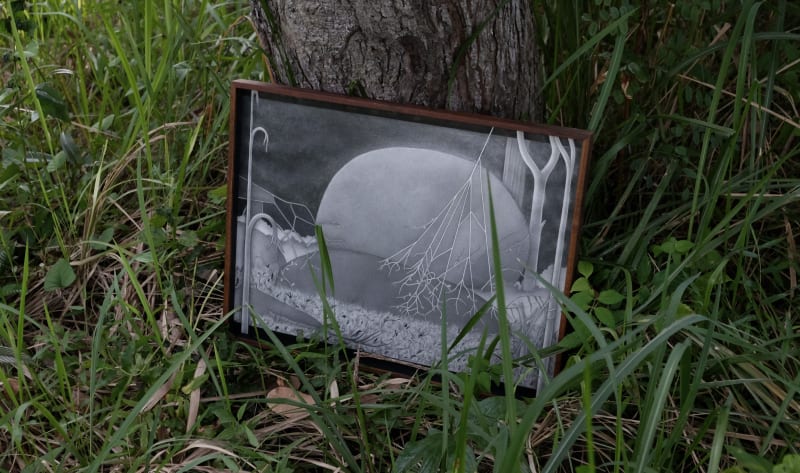

"Untethered to ideologies, the ritualistic forms expressed by artists today make space to navigate a present in flux. Take Aracha Cholitgul’s ‘Little Sundown Resort’ project (2023-ongoing), which focuses on the shifting landscape of Koh Pha-ngan island. Showing with Nova Contemporary, drawings of stones presented as if they were stills from a film compose the project’s first chapter, Moving Images of Stones on the Island. They bear witness to what tourism, development, and gentrification has done to the island in the 21st century – particularly, as Cholitgul points out, after COVID-19, when locals have had to sell their land to make ends meet. ‘It’s quite traumatizing to see other Thai people slowly forced out of the island because they can’t afford to live here,’ the artist says. ‘Moving Images of Stones on the Island acts as a reflection and introduction to the current landscape through the perspective of a troubled human being trying to navigate life on the island."